Director: Alejandro G. Inarritu (2016)

Gripping, grisly and grizzly, this epic revenge western is the first must see film of 2016.

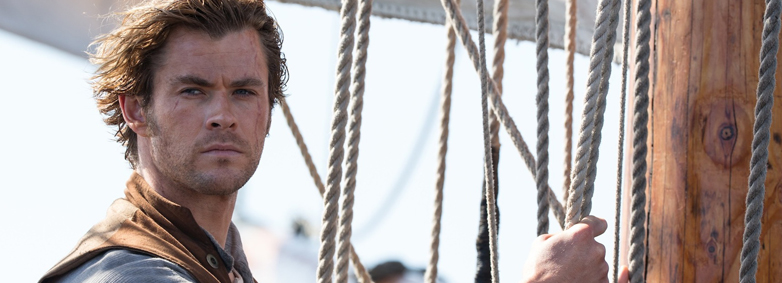

Leonardo DiCaprio goes hunting for the best actor Oscar in this thrilling and icily apocalyptic adventure.

Despite his best efforts, notably his portrayal of a ravenous financier in The Wolf of Wall Street (2014), the Academy award has so far eluded him.

But on this form as fur trapper and explorer Hugh Glass, there’s every chance he’ll bag it.

While on an expedition in the uncharted Northern frontier, Glass is brutally mauled by a bear.

I could barely endure the ferocious scene as the angry beast tears away at Glass with it’s hot breath steaming the camera lens.

He just about survives only to see his son murdered and find himself abandoned.

Driven by his pain and suffering Glass begins a 200 mile odyssey across the wild, wild west, intent on killing the man who betrayed him.

On the lonesome trail Glass endures being washed away, buried alive, burned and stabbed.

There’s visceral violence and dialogue as sparse and unforgiving as the environment.

For those who aren’t convinced by DiCaprio’s acting ability, they should see how much he conveys here while speaking very little.

Meanwhile as an old native American leads a war party in search of his missing daughter, a party of French hunters are wreaking destruction across the landscape and complicating Glass’ progress.

A huddle of orphaned children, murdered sons, forgotten wives and rich fathers are offered as a limited backstory for various characters, tying them together in a litany of loss.

With long stretches of screen time dialogue free, character is conveyed though action. The principals are aware of the conflicts in the damnable choices they face.

A trio of British actors offer brilliant support to DiCaprio.

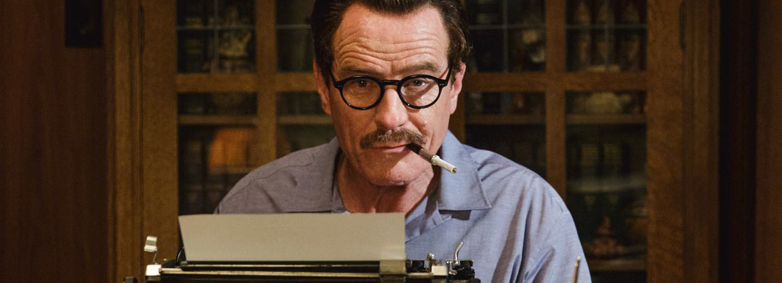

With Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), Legend (2015) and Locke (2014) Tom Hardy is enjoying a great run of projects.

He plays the pipe smoking trapper Fitzgerald, a vicious pragmatist rather than evil incarnate.

Even more blessed with an uncanny knack of choosing great projects is the likeable, versatile and always interesting Domhnall Gleeson.

He comes of age as Captain Henry, the leader of the hunting expedition who is out of his depth.

Will Poulter is Jim Bridger, the youngest of the troop and arguably the closest it carries to a conscience.

Editor Stephen Mirrione previously worked on Birdman (2015) and won an Oscar for Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic (2000).

His signature long edits create an intensive immediacy and putting us uncomfortably in the centre of the action.

Cinematography Emmanuel Lubezki won consecutive Oscars for Gravity (2014) and Birdman (2015) and may well earn a third here.

Director Inarritu won best film, director and screenplay Oscars for Birdman (2015) and it would it not be undeserved if he repeated the trick in 2016, though in the adapted screenplay not original screenplay category as in Birdman (2015).

As in Birdman (2015) Lubezki’s ceaselessly circling camera work puts us in the middle of the action whether on horseback, on boats or underwater.

We witness an avalanche, rape, castration, shoot outs, knife fights, a hanging, a massacre and the aftermath of several more.

The landscape is alive with moose, wolves, horses, fish, buffalo and ants, demonstrating how ill geared humanity is to surviving in this fierce winter wonderland.

Set in Wyoming the production went snow chasing through Canada, the United States and Argentina to achieve the frostbitten extremes of the American frontier.

Grounded in fire, rock and ice, the elemental force of the film is captured in blues,whites and greys, with explosive moments of orange punctuating the palette.

Visual reference points are Robert Altman’s McCabe And Mrs Miller (1971) and Werner Herzog’s Aguirre: Wrath of God (1972).

Thematically the story draws on Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000) and John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). It is based on Michael Punke’s 2002 novel of the same name inspired by the exploits of the real Hugh Glass.

Ideas of commerce and colonisation swirl around the contemporary issues of the ownership of natural resources, the conflict between races and the role of the military in a civil society.

The Revenant means ‘the returned’ and refers to a person who comes back from the dead.

It sounds like a combination of ‘revenge’ and ‘covenant’, god’s code of behaviour issued to Moses in the Old Testament.

These two ideas compete within Glass for supremacy as he battles towards his prey.

Glimpses of Glass’ late wife through fragments of memories remind us of his spirituality even as he symbolically swathes himself in bearskin.

Eating its flesh shows his growing connection with the environment but also suggests a departure from the rational to an animal state.

In fables there is always a limit to how long one can adopt the shape of another creature before losing one’s humanity for ever.

Glass’ quest for revenge becomes a battle for his soul from which he may never recover.

A chilling final frame questions the audience as to how they would behave in Glass’ circumstances. It’s an electrifying end to a remarkably realised endeavour.

★★★★★

@ChrisHunneysett

You must be logged in to post a comment.