Breathtaking in its pioneering use of underwater photography, this silent two-hour feature is a globetrotting epic of action adventure, romance and comedy, and though contains some problematic elements, it’s an early high water mark in Hollywood spectacle, an impressive early entry into the canon of Jules Verne adaptations, and by far the biggest box office success of its year of release.

An adaptation of not one, but two major works of the man often referred to as the ‘Father of science fiction’, 20,000 Leagues combines elements of two of Verne’s novels, namely 1871’s adventure, 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, and 1875’s semi-sequel, The Mysterious Island, bringing together the twin adventures of Verne’s most celebrated creation, the mercurial billionaire genius inventor and subaquatic explorer, Captain Nemo.

From this rich material we experience a tale of rape, murder, child abuse, kidnap, and betrayals. Plus there are fistfights, a sea battle, a colonial uprising, a reconciliation of long lost family members, as well as ghosts, devils, and real live sharks.

For those not overly familiar with the source material, 20,000 Leagues is set in 1866, and sees Professor Aronnax and two male companions kidnapped by a middle aged and vigorous Nemo, who takes his captives sailing around the globe in his technologically advanced submarine, The Nautilus. Meanwhile The Mysterious Island is set during the US Civil War (1861-1865) sees a group of Union prisoners escape by hot air balloon to the titular Pacific Ocean island, where an elderly and dying Nemo secretly assists their survival and only reveals his presence at the end of the novel.

When it came to adapting this material for his 1916 production, for the sake of cinematic expediency, Verne’s appallingly contradictory timeframe is rightfully given the old heave-ho by Scottish director and screenwriter Stuart Paton, who sensibly also jettisons much of the ballast of Verne’s ponderous scientific explanations, and in true Hollywood fashion introduces female characters to provide romance and intrigue to Verne’s nearly all-male world.

Paton also introduces female characters such as Aronnax’s adult niece, who replaces the manservant Conseil as one of Aronnax’s companions, and on the Mysterious Island there is a young woman wearing a leopard print dress, who replaces the male castaway of the novel. Although Aronnax’s niece plays little part in the film, the female castaway ‘A Child of Nature’ as she’s billed, is central to the story. And yes, though much of what she does is invented by Paton, there’s no denying it’s an exuberant and captivating performance by actress Jane Gail.

Paton’s script cuts back and forth between the parallel stories of Aronnax on The Nautilus, and the escaped balloonists, eventually bringing the plot-lines together in a terrifically staged finale before ending on a note of poignant dignity which I suspect Verne would approve. This is a great example of how to ruthlessly hack an unwieldy source material into a platform for great cinema.

Typical of the era, the Asian characters of Nemo and ‘A Child of Nature’ are played in brownface, a now rightfully discredited technique. Yet A Child of Nature’s inclusion allows for an inter-racial Caucasian-Asian romance between her and a balloonist, which is quite the something in a film released the year after D. W. Griffith’s infamously racist, The Birth of a Nation.

This romance doesn’t occur in Verne, and is possibly inspired by Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which features a crew of shipwrecked men encountering a beautiful girl and her wizard father on a desert island. Nemo is explicably described as a ‘wizard’, and also deals with issues of colonialism and race.

On another note, the romance as portrayed may not be interpreted as such as by a modern audience, there’s no explicit kissing for example. However if we the audience are expected and required to interpret two rape scenes as rape scenes, and not ‘just’ assaults, then we’re similarly beholden to interpret their flirtatious behaviour in scenes as romantic and sexual in intent.

However the film is less kind to the balloonist, Neb, Verne’s sole Black character in these books. Treated with jaw-dropping racism in the novel, The Mysterious Island, this film introduces Neb only to quickly cut him from the film. This happens so alarmingly abruptly I first assumed the copy of the film I was watching was missing a reel.

However Neb’s very noticeably absent from an important scene at the end where the cast are brought together. We can only speculate what happened to poor Neb, and why he ended up so ruthlessly dispatched to the cutting room floor. The treatment of Neb and the casting of Nemo in subsequent adaptations is something I’ll address in another post.

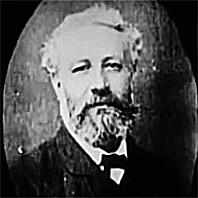

Nemo himself stands alongside Sherlock Holmes as a great example of a literary character whose cultural existence has a life beyond his creator, and who’s longevity in the popular consciousness relies far more on countless and varied media interpretations for fame than for people reading the books. Many more people will be familiar with their names than will have ever read the source material.

Featured in graphic novels, cartoons and now in video games, such the 2015 Japanese mobile game Fate/Grand Order, Nemo’s been portrayed by Russian, Egyptian, Czech, and Puerto Rican actors, as well as by Indian and Pakistani ones. And it’s in The Mysterious Island, not the more famous 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, that Verne reveals Nemo is an Indian Prince whose wife and child was murdered by the British during the historical Indian Rebellion of 1857, also known as The First War of Independence.

It transpires Nemo is really Prince Dakkar, son of the Hindu raja of Bundelkhand, and a descendant of the Muslim Sultan Fateh Ali Khan Tipu of the Kingdom of Mysore. When Verne was writing The British Empire and the Third French Republic were competing for global superiority, and painting the British as the villains would no doubt be a winning strategy for the French writer, and not damage his sales either at home or in the US, a country often celebrated and the source of heroic characters in Verne’s work.

In 1914 when filming of this version of Nemo began production, the world had changed again, with The Great War, as The First World War was then known, was beginning in earnest. And here Nemo’s story is fudged considerably by Paton, who removes some historical context and shifts the blame away from the British.

We learn instead that Nemo’s life in aquatic exile aboard The Nautilus began after he was falsely accused of inciting a rebellion in the unnamed Asian country of his birth, one under colonial rule by an unnamed European. A map on the wall in one scene indicates it is indeed India. However the military uniforms appear more generically European, perhaps French or German than British. It’s possible all Europe colonialism looks the same to Americans. I’m not an expert in military uniform and perhaps the costume department had a surfeit of those costumes readily available.

Nemo’s tragic backstory role in the rebellion is relegated by Verne to a couple of paragraphs, however here it’s portrayed in flashback at the end of the film, with the rebellion allowing for some impressive sets and crowded battle scenes. Rather than being purpose built the sets look suspiciously as if they were borrowed from another production, but they add to the sense of spectacle and allow for a fittingly huge finale.

Despite readers of The Mysterious Island being familiar with Nemo’s origin story, interestingly, and presumably for publicity purposes, a title card claims Prince Daakar’s {sic} tragic story has never been told by Verne. The author died in 1905 and so wasn’t available to dispute the claim.

The title cards are fascinating in themselves. The first grandly proclaims this to be ‘The First Submarine Photoplay Ever Filmed’ which is catnip to fans of submarine films such as myself, as well as making this film hugely significant in the realms of special effects and cinematography.

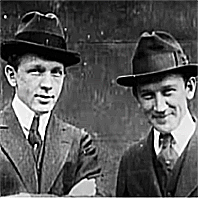

The second tells us it was directed by Stuart Paton and photographed by Eugene Gaudio, then the third card states the submarine photography was possible by using the inventions of the Williamson brothers, who ‘alone have solved the secret of under-the-ocean photography’ and we’re introduced to the Ernest and George Williamson themselves, who smilingly doff their hats for us. They can be justly proud of their work. And then we’re shown a still photograph of Verne himself, a shame he wasn’t around to see himself honoured so. Imagine if JRR Tolkien had been so honoured by Peter Jackson in his magnificent 2001-2003 Lord of the Rings trilogy.

There’s a strong commitment to exterior location filming, and the underwater work is phenomenal. An astonishing underwater shark hunting trip is executed with the type of contemporary disregard for health and safety associated with the worst excesses of Cecil B. DeMille, which makes for a very exciting watch.

This undersea footage was shot in the Bahamas where Walt Disney 38 years later shot his 1954 James Mason-starring version of 20,000 Leagues, and for the same reasons, a great deal of natural light and very clear water.

In 1916, underwater cameras weren’t used to shoot the underwater scenes staged in shallow sunlit waters, but the Williamson brothers used a system of watertight tubes and mirrors to allow the camera to shoot reflected images of the scenes as they took place.

The exterior of The Nautilus looks very close to how Verne described it, a very smooth cylindrical hull with a wooden platform on top for the crew to stand on. Whether in or on the water, it’s these scenes that make the film such a joy.

According to IMDB.com, 20,000 Leagues was produced at the unadjusted eye-watering cost of $500,000 by The Universal Film Manufacturing Company, a precursor to todays Universal Pictures. And it took a staggering $8million at the box office, comfortably outgrossing the second biggest hit of the year which could only scrape together $2.18million, thank you and goodnight, D. W. Griffith’s non-apology of an historical epic, Intolerance.

For the pioneering underwater photography which captures Verne’s love of technological innovation, this is madly impressive. When added to it being respectful and faithful to the source while offering spectacle, romance, comedy and action adventure, this sets an extraordinarily high bar that many of the subsequent adaptations of Verne fail to reach.

Nemo’s Fury is an exciting digital reinvention of Jules Verne’s classic steampunk adventure novel, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Download for free to your smartphone or tablet, search your app store for ‘Nemo’s Fury’.

A mobile interactive fiction game employing a bespoke combat system and hundreds of original illustrations, Nemo’s Fury is inspired by the 1980’s role-playing gamebooks such as ‘The Warlock of Firetop Mountain’, of the Fighting Fantasy series which celebrated its fortieth anniversary last year.

Each player joins the legendary Captain Nemo on board his fabulous submarine, the Nautilus, on a wild voyage of adventure, intrigue, loyalty, and betrayal.

There’s mayhem, monsters, maelstroms and murder as Nemo takes you from the South Pacific to the Northern Atlantic via Antartica and the Red Sea. And if they survive long enough, the player will of course fight a giant squid.

Available on your smartphone or tablet, (but not yet your desktop), click on your app store below

Or go to Nemo’s Fury for more info

You must be logged in to post a comment.