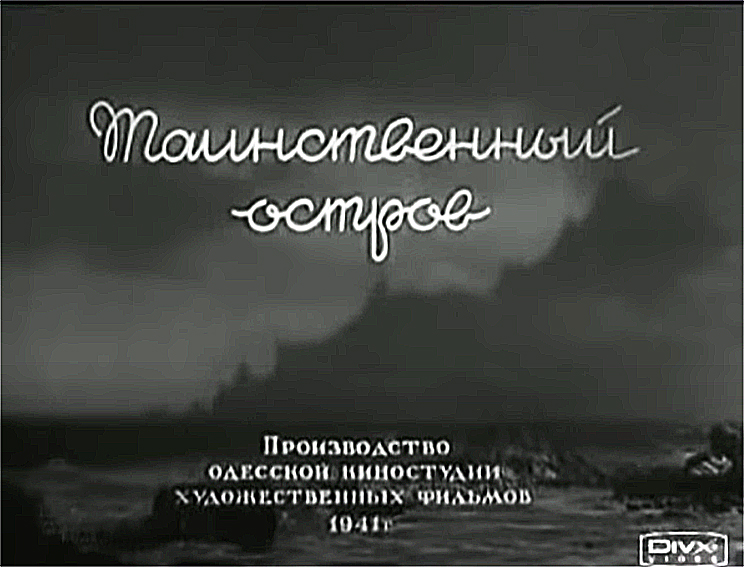

This definitive big screen big budget adaptation of Jules Verne’s 1870 science fiction novel is a handsomely-staged family adventure mostly remembered for Kirk Douglas star performance and fabulous design. Yet there’s also a surprising degree of Cold War concerns bubbling beneath the surface, making this hugely entertaining version far more interesting than most subsequent adaptations.

Running at just over two hours, the filmmakers sensibly abandon the vast majority of Verne’s self-aggrandising scientific posturing in successful pursuit of huge box office success.

Broadly faithful to the wide-eyed adventurous spirit and plot of Verne, we follow a Professor, his servant and a harpooner, who’re kidnapped at sea by the mercurial and revenge-driven submariner, Captain Nemo, and join him for several escapades onboard his submarine, the Nautilus, while plotting their own escape.

The trio were recruited by the US government in San Francisco, a reassuringly ‘Western’ opening location for the audience, before sailing to the South seas to confirm or deny the existence of a sea monster which has been sinking ships.

The smooth but shady US recruiting agents want to to beat other nations in capturing this sea monster in order to establish and exploit any military capability it may possess. And thus the 1950’s audience is immediately plunged into an allegory of the post-war arms race with the Soviet Union.

Whereas the French writer Verne had the US government employ Professor Aronnax in order to have a compatriot hero to appeal to Verne’s home readership, here Aronnax is not only valued as a scientific advisor but his nationality offers the cover of political neutrality to a US military expedition in contested overseas territory.

This accurately reflects the use of other nation proxies to project US power and further its national interests during the then developing Cold War and establishes a degree of paranoia which the film later develops when it deploys mushroom cloud imagery.

However while the film demonstrates the destructive power of nuclear weapons, it also offers an argument in their favour and sympathy to those who developed them. More of which later.

Peter Lorre is a wonderfully cowardly cynic as Conseil, servant to the dull Professor Aronnax, played by Paul Lukas, who’s performance suggests the Hungarian actor fully understands he’s not there to upstage the top-billed star, Kirk Douglas, who plays the two-fisted harpooner, Ned Land.

Already a household name and a double best actor nominee for 1949’s Champion, and 1952’s The Bad and the Beautiful, Douglas perfectly understands the material, and delivers a wonderful cigar- chomping, scenery-chewing and scene-stealing performance, which screams ‘movie star’.

A role tailor-made to demonstrate his athleticism, humour, charisma and boisterous comic ability, Douglas also commits fully to the required singing and dancing, and if he’s not the greatest at either, well I doubt there was anyone on set with the authority or nerve to tell him.

It would be hard to find a scene in his career more joyous than the one where he shares a song and kiss with a pet seal, and their duet is a piece of wonder that is comic, angry and tender. If only Douglas had always been this generous to his co-stars.

And in the fight scenes you have to worry for the stunt team as the 38 year old Douglas, still six years from playing rebellious Roman slave, Spartacus, seems determined to never pull his punches. At times he seems to be auditioning for a live action version of Popeye the sailor.

Director Robert Fleischer would re-team with Douglas two years later with The Vikings, and in a lengthy career, Fleischer would go on to make 1967’s serial killer drama, The Boston Strangler, 1973’s sci-fi conspiracy thriller, Solyent Green, 1980’s musical remake, The Jazz Singer, and 1984’s Sword-and -Sorcery sequel, Conan the Destroyer.

The mysterious Captain Nemo is revealed by turns a brilliant scientist, ruthless, an intellectual and a sympathetic victim, an ‘other’, i.e. a non-WASP, who serves his ‘guests’ ‘unusual’ food.

All this is true to Verne, but although early film incarnations of Verne’s novel recognised Nemo’s royal identity as an Indian prince, here Nemo is played by white British actor, James Mason. His other major role that year was alongside Judy Garland, in A Star is Born.

Here the template is set for subsequent interpretations to whitewash the role and those who follow in Mason’s footsteps include the very non-Indian actors, Herbert Lom, Michael Caine and Patrick Stewart.

But Mason’s character is more interesting than many later interpretations, with Nemo’s non-white otherness being coded as Jewish, and Nemo’s struggle for revenge on the British empire being substituted for the fight to use nuclear power to defend the state of Israel.

Verne’s Nemo wants revenge for the slaughter of his wife and child by the British during the 1857 Indian War of Independence, but Mason’s Nemo is a widowed state-less refugee, a survivor of slavery in a mine producing phosphate for war weapons.

We later see the mine which is visibly intended to evoke the Holocaust of the Second World War. Nemo was sent there after refusing to divulge the secret of the power source of the Nautilus, implied as nuclear power. Anyone with a passing knowledge of the European Jewish emigre scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project and its development of the first nuclear bombs, will be able to see the intended parallels.

The world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, USS Nautilus (SSN-571) was delivered to the US Navy in 1955. Thus Nemo using nuclear power for world peace dovetails nicely with contemporary US military policy, he’s also trying to protect his island sanctuary from assault, a haven which can be read as a proxy for the recently established state of Israel. Nemo repeats, ‘There is hope for the future, when the world is ready for a new and better life then all this will someday come to pass in God’s good time.’

There is hope for the future, when the world is ready for a new and better life then all this will someday come to pass in God’s good time.

The giant squid which threatens the Nautilus is direct from Verne’s novel, but allied to the theme of nuclear power aligns 20,000 Leagues with sci-fi monster movies of the day, which saw humanity threatened by insects and other creatures mutated to enormous size by nuclear sources.

Nuclear paranoia of sci-fi classic, The Day The Earth Stood Still, had been released in 1953, and Ray Harryhausen’s 1955 The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, saw a hibernating dinosaur released by an atomic blast to terrorise the world.

Released the same year as 20,000 Leagues, Them! saw huge radiation-affected ants bring terror to the US, and Godzilla stomped into cinemas in 1954. The US was threatened by aliens in 1953’s It Came From Outer Space, and by giant spiders in 1955’s Tarantula! Whether aliens, monsters or giant insects, and whether nuclear powered or not, 1954 was hotbed of paranoia about the Soviet nuclear threat.

It must also be noted that 1954 was the height of McCarthyism, the Red Scare, and the communist ‘witch-hunts’ in Hollywood. Ever the patriot, Walt Disney had testified before the HUAC hearings in 1947, and it’s interesting that the ultimately sympathetic Nemo argues in favour of the benefits of nuclear power, and the film ends on an audience-reassuring note in faith in god, science and the future.

The nuclear subtext is dressed up in art direction and special effects and 20,000 Leagues deservedly won Oscars in both those categories, as well as scoring a nom for the editing.

The sets, model ships and submarines are great and the locations are epic, representing Hollywood at the top of its game. If the Nautilus is more a metallic fish than the tube of Verne’s imagination, the submarine is a gorgeous steampunk creation, with brass fittings, red upholstery and a magnificent organ. And long before Spielberg’s 1993 dinosaur adventure Jurassic Park, the animatronic work of the giant squid is spectacular.

Although stock footage of whales and dolphins is occasionally mixed in with scenes on deck clearly filmed in a studio, there’s an impressive commitment to the underwater diving sequences, made when aqua diving was a novelty not an easily-accessible holiday activity.

These sequences were filmed in the photogenic waters of the Caribbean, as was the silent 1916 version of 20,000 Leagues, and if that gives some sections the air of a travelogue, it’s worth remembering foreign travel was an expensive luxury at the time and this form of visual escapism was very much intended to drive box office.

Still, the shark attack is very impressive and the location work helps retain Verne’s tone of wide-eyed wonder and his view of the sea as a resource to be worked. Mind you, the man-handling of crabs and giant turtles by the underwater performers wouldn’t be allowed today.

Sadly the same couldn’t said for the depiction of the South sea islanders, who Nemo describes as ‘cannibals’, and whose appearance is played for laughs, and their portrayal is no less sophisticated than similarly portrayed people in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise.

And though Nemo drolly asserts the ‘cannibals’ right to attack the Nautilus, true to the book he then defends the Nautilus with electric shock treatment.

Similarly to the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, there’s no denying the scale of the action is impressive, perhaps ever more so than then, in our CGI era. And seeing Douglas run through the jungle reminds us of his son Michael, in 1984’s Romancing the Stone.

Despite the film throwing a series of grandly staged set-pieces at us, it’s possible a modern multiplex audience may find the pace plodding. Yet the crowd-pleasing ticking clock plot and punch-ups of the finale are pure Hollywood entertainment, harking back to Flash Gordon serials of the 1930s, and anticipating the missions of 007 of the following decades.

And though the final scene of the novel is downbeat, the filmmakers compromise by cleaving closely to Verne yet also providing a note of uplift, in which Kirk Douglas’s seal is seen to survive, and Nemo is given the last word.

To do this a cinematic sleight of hand is used which would be echoed two years later in Elvis Presley’s big screen debut, Love Me Tender. The enduring fascination with and longevity in popular culture of Verne’s greatest creation, Captain Nemo, lies with his mercurial nature which allows for continual reinvention. However, never did I think when I began writing this that I would end with a comparison with the King of Rock ’n’ Roll.

Available on Disney+.

You must be logged in to post a comment.