Director: Stephen Frears (2016)

Big screen diva Meryl Streep launches a ferocious assault on your ears in this biopic of the worlds worst opera singer.

As the title character, her ignorance of a lack of talent is a punishing off note joke.

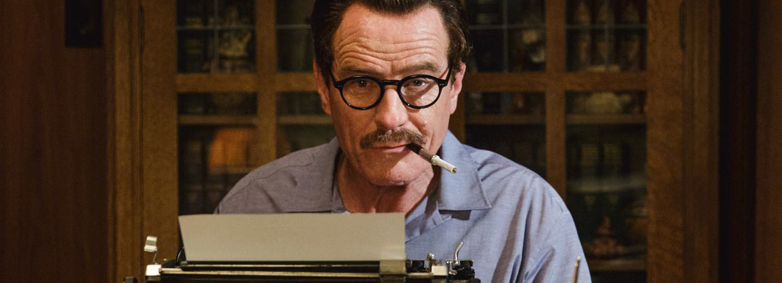

But if you can endure Streep’s cacophony of comic caterwauling, there’s a lot of enjoyment in the tender chemistry created with her on screen husband St. Clair Bayfield, played by Hugh Grant.

It’s New York 1944 and heiress Florence is an overly generous patron of the arts whose entourage exploits her good nature for cash.

Determined to aid the war effort, she books herself a gig at Carnegie Hall and gives a thousand servicemen free tickets.

This threatens St. Clair’s luxurious life as neither he, tutors or muscians dare tell Florence the painful truth about her lack of ability, for fear of being put out on their arias.

Director Stephen Frears’ lack of visual ambition is compensated by adhering to the narrative and focusing on character.

He’s rewarded with two marvellous performances as the leads stretch their throats in extraordinary ways.

Grant has never better. With the fading of his still considerable leading man looks, his tremendous talent shines ever brighter. He gave a light comic masterclass in The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (2015) and here he dances like a young James Stewart.

Streep was last seen singing on screen as a bar room rocker in the weak Ricki And The Flash (2015) and here gives a performance of grand neurotic eccentricity.

The stars essay a complex relationship while the script saves its mockery for the sycophants who surround them.

Rebecca Ferguson is under served as St. Clair’s lover but Nina Arianda is show stopping as a ticking blonde bombshell, threatening blow up the whole charade whenever she speaks her mind.

This is the second telling of the story this year, after the French language version Marguerite (2016) which won 4 prestigious Cesar awards.

This version is undemanding with broad appeal, and you don’t have to appreciate opera to enjoy it.

★★★☆☆