Director: James Vanderbilt (2016)

Best switch channels than tune into this ham fisted drama about the fall of real life TV journalists.

A self serving and poorly constructed script plus an over wrought tone destroys the solid work of stars Robert Redford and Cate Blanchett.

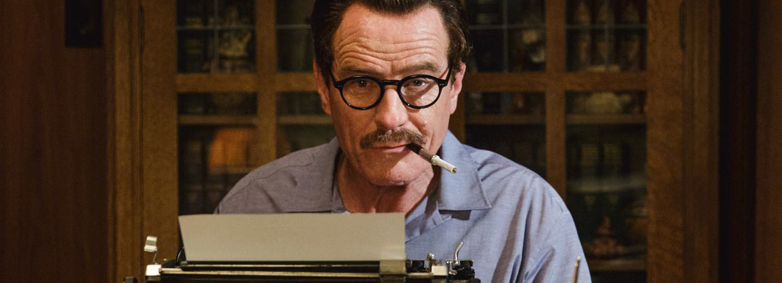

He plays venerable journalist and avuncular TV anchorman Dan Rather, a surrogate father to his producer Mary Mapes.

Under ratings pressure she breaks a big story about the military service record of the young George W. Bush who is seeking a second Presidential term.

But when the story unravels due to a dodgy dossier, unreliable witnesses and thin evidence, the journalists become the story and must fight to save their careers.

Mary is a driven, intelligent, and contradictory but is an unsympathetic figure who prefers to cry conspiracy than recognise her own weaknesses.

Thinly written supporting characters have barely there interactions before being forgotten about.

The film touches on several styles and genres, wildly snatching at a tone to give meaning to the dull drama playing out.

In the style of a heist movie, a crack team of journalists is assembled but given absolutely nothing to do before quietly slipping out of the movie.

It then becomes a busily plodding procedural movie with moments of courtroom and sporting drama.

Despite protestations of political impartiality, rival TV networks seem to fighting a proxy election campaign with the CBS employees firmly in the Democratic Party anti-Bush camp.

The script makes grandiose claims about the power of journalists to influence elections but with a week being a long time in politics, the decade old story has little contemporary resonance now Bush is long out of high office.

There is none of the relevancy of the recent Best Picture Oscar winning Spotlight (2016). It also lacks that films extraordinarily rigorous storytelling.

In bizarre scenes devoid of irony, ordinary citizens are seen gazing in wonder at Dan read the news. They’re primates reaching out to the monolith in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Truth is a hymn to the memory of Rather whose name means little to a UK audience. It also a lament for the good old days when the news wasn’t subject to a political agenda prescribed by wealthy owners. (Ha!)

You must be logged in to post a comment.